Initial Submission Window: 1 October 2025- 31 October 2025

Guest Editors

- Marlys Christianson, University of Toronto

- Brian Hilligoss, University of Arizona

- Christopher Myers, Johns Hopkins University (AMD Associate Editor)

- Kathleen Sutcliffe, Johns Hopkins University

- Timothy Vogus, Vanderbilt University

Overview

Recent years have seen a cascade of changes to work organizations, impacting every facet of organizational life, from the nature of employee collaboration to the fundamental structure and boundaries of what it means to be an “organization.” These changes are of interest to management and organizational scholars, inviting empirical research that can help illuminate new or under-explored organizational phenomena in ways that update, refine, and advance the field’s understanding of the modern world of work.

Nowhere are these evolving, complex, and dynamic features of work organizations more apparent than in the domain of health care, as seen in the increased attention to human and organizational determinants of health care since the turn of the century (e.g., To Err is Human, 2000), more recent evolutions in health care structure and financing (e.g., through the 2010 Affordable Care Act in the United States), and the turbulence of the global COVID-19 pandemic (and its associated disruptions to the world of work). Clearly, health care has seen an incredible array of challenges and advancements in the recent past, and the future promises more of the same.

Health care is an inherently broad domain, encompassing not only organizations that directly provide health care to patients, but also an array of related industries, regulators, funders, and professions that together create a maze of organizational and interpersonal interdependencies. As Ramanujam and Rousseau (2006) note, the health care setting is characterized by multiple (and at times conflicting) missions, a multi-professional workforce, complex external environments (with a wide range of stakeholders), and the provision of inherently complex, dynamic work tasks. Moreover, by most metrics (GDP, employment, spending, utilization, etc.), health care is a dominant sector of the global economy, and is a domain where failures of organization and management have dire consequences (Mayo, Myers, Sutcliffe, 2021; Ramanujam & Rousseau, 2006).

Organizational Science and Health Care

Given these features, health care contexts represent an incredibly valuable research domain for management scholars interested in a wide range of topics and levels of analysis. As DiBenigno and D’Aunno (2024) recently commented, health care “has it all,” with prior work exploring this context from macro-, meso-, and micro-level perspectives to generate valuable insights. Given the inherently interdisciplinary nature of studying organizational phenomena in the health care setting, past work has spanned a range of disciplines, often bridging domains of organizational scholarship, industrial relations, and health care scholarship (e.g., health policy, health services research, medicine, medical sociology, and nursing), yielding key insights for theory and practice.

For example, integrating across these disciplines, we know that organizational strategic choices have important implications for both adherence to evidence-based practices and financial outcomes (e.g., Everson, Lee, & Adler-Milstein, 2016; Lee & Kapoor, 2017) and that institutional and network factors influence the adoption of new health innovations and technologies across the industry (e.g., D’Aunno, Succi, & Alexander, 2000; Westphal, Gulati, & Shortell, 1997). We also know that team-based care can be important for enhancing the provision of care (e.g., Reddy et al., 2018; Reiss-Brennan et al., 2016), and that factors such as experience working together, team scaffolds, boundary management, and training can enhance health care team effectiveness (e.g., Hughes et al., 2016; Luciano et al., 2018; Mayo, 2022; Valentine & Edmondson, 2015). At the individual level, we have some understanding of the impact of health care workers’ strong professional identities (e.g., DiBenigno, 2022; Pratt, Rockmann, & Kauffman, 2006) and how health care workers’ job satisfaction is enhanced by perceptions about leadership, teamwork, and justice (e.g., Perry et al., 2018; Djukic et al., 2017; Sheridan et al., 2018; Trybou et al., 2016).

The examples above provide just a sampling of the ways in which organizational phenomena can be studied and understood in health care settings in ways that shed light on the experience of work in modern organizations. Indeed, in their recent review of the field, Mayo and colleagues (2021) take stock of the body of scholarship in both management- and health-focused journals that address organizational phenomena, detailing some of the more well-studied topics across the field (specifically organizational change, learning, coordination/collaboration, teaming, and performance).

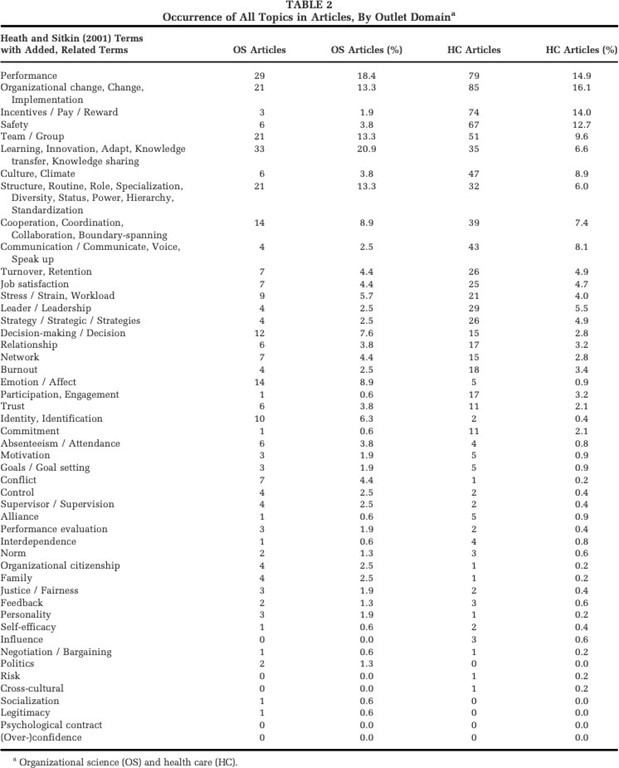

This recent review, however, also highlights the much longer list of organizational topics that have received comparatively less attention in past research on health care (see Mayo et al., 2021; Table 2 – provided as an appendix to this Call for Papers). In addition, Mayo and colleagues (2021) highlight the fragmentation and dispersion of existing research in the field across different outlets (i.e., management vs. health care journals) and different research orientations. Specifically, they highlight a tendency, often observed in research published in management journals, for researchers to treat health care as merely an incidental context from which they seek to glean universally generalizable theory about organizing processes (which they term “organizational science in health care”). This contrasts with a tendency, observed more frequently in health care journals, to deploy organizational concepts to solve specific problems and generate insights unique to a particular health care domain or organization (in pursuit of what the authors term an “organizational science of health care”; Mayo et al., 2021). Each of these approaches has advantages and drawbacks, leading the authors to conclude their review with a call for more work that stands in between these extant approaches – adopting an “organizational science and health care” orientation that balances generalizability and contextualization and offers insights for both organizing and organizations in health care and beyond (Mayo et al., 2021).

Goals of the Special Issue

Given the list of organizational phenomena unexplored in health care settings, as well as the disparate approaches taken in prior work, the goals of this special issue are to publish novel empirical explorations while taking seriously the invitation to balance organizational science and health care – in other words, work that takes seriously both the charge to develop a richly contextualized understanding of a key empirical discovery and develop its implications for a more generalized understanding of work, strategy, organizations, management, and institutions.

We see these as complementary goals – recognizing that generalizability is enhanced, rather than harmed, by careful attention to contextualizing research (Johns, 2006; Rousseau & Fried, 2001) – and ones that are particularly well-suited to the nature of AMD as an outlet for “articles motivated by research questions that address compelling and underexplored phenomena … that present clear and compelling discoveries: empirical findings that challenge existing assumptions while opening new theoretical paths or that otherwise promote future, ‘down-the-road,’ theorizing.” (AMD website)

We invite papers that study any organizational phenomena relevant to the experience and functioning of health care (broadly defined) for this special issue. This could include “classic” topics central to organizational scholarship that are particularly visible or impactful, but still poorly understood, in health care (i.e., many of the topics listed in Table 2 of Mayo et al., 2021; see Appendix). It also includes phenomena that are particular to health care settings, but might carry important implications for all organizational environments (e.g., the study of handoffs and transitions, which are central to health care delivery settings, but are increasingly occurring in many organizations that switch to project-based work coordinated across disparate teams or units; Hilligoss & Vogus, 2015; LeBaron et al., 2016).

We intentionally take a “big tent” view of health care, recognizing that care is increasingly delivered outside of clinical settings and organizations (including at home or in the workplace); that this care relies on inputs from a broad range of industries, professions, and individuals; and that the health of the workforce is increasingly considered a core responsibility of any organization’s leadership (e.g., via a corporate Chief Medical Officer; Myers, Polsky, & Desai, 2022). We thus welcome submissions that consider a variety of dimensions of health and health care (including mental health) at any level of analysis. We also encourage submissions that involve and engage practitioners in the development and presentation of discoveries (for more, see the recent AMD “From the Editors” essay on practitioner involvement in empirical research; Ben-Menahem, 2024).

Sample Topics

The topics listed below present a non-exhaustive list of empirical phenomena in health care that might be appropriate for this special issue. We, however, stress again that the scope for this special issue is intentionally quite broad and we welcome submissions from a broad range of conceptual traditions, methods, and domains. Moreover, most of the topics below are subject to empirical exploration at different levels of analysis or across multiple levels of analysis (as is true of many aspects of health care). In each domain, research might fruitfully explore the implications for workers and the workforce, the consequences for organizations or patients (e.g., their experience of care and quality of care), or the impact of relevant policy, industry, and organizational conditions. Questions about the suitability of a particular topic should be directed to a member of the editorial team.

- Evolving Intersections of Health Care and Work

- Introduction of AI in health and health care

- Use of new technologies (e.g., robotics, additive manufacturing) in health care

- Disruptive events and health crises (e.g., COVID-19)

- The individual, organizational, and sectoral/institutional consequences of operating in a politically charged and polarized domain

- The competing ethics of health care and care delivery (e.g., professional, organizational, and personal ethics)

- Structural Shifts in Health Care

- New ownership and governance structures (e.g., private equity investments)

- Funding, payment, and regulatory shifts affecting health care

- Provision of health services (e.g., caregiving, mental health care) in non-health organizations and work settings

- Personalized medicine

- Complex system dynamics and achieving safe, reliable care

- Trends in Health Care Delivery

- Emergence of new professions (or proto-professions like community health workers), evolution of professional roles, and changing scope-of-practice

- New work arrangements (e.g., remote work, “travel” nursing)

- New modalities of care delivery (e.g., virtual health care and telemedicine)

- Work implications of home health care and long-term care providers

- Workforce composition and demographics, workload, and burnout

- Globalization of the health care workforce

- Learning and decision-making in the face of limited evidence (e.g., COVID-19 treatment)

About AMD

AMD is a premier journal for the empirical exploration of data describing or investigating compelling phenomena. AMD is not a journal for deductive theorizing or hypothesis testing. Authors are encouraged to present findings without the need to “reverse engineer” any theoretical framework or hypotheses. AMD publishes discoveries resulting from both quantitative and qualitative data sources. AMD articles are phenomenon-forward rather than theory-forward. This means that AMD papers look quite different in comparison to articles sent to other empirical journals. The goal at the front end of an AMD paper should primarily be to demonstrate the novelty/interestingness of the phenomenon and why current theory fails to explain the phenomenon. It is in the discussion of an AMD paper where a plausible theoretical explanation—the theoretical contribution—is provided. The goal for every AMD paper is that the discoveries derived from empirical exploration open new lines of research inquiry. For further information about the goals of AMD, we encourage potential submitters to review recent “From-the-Editors” articles from AMD’s current and previous Editors (Miller, 2024; Rockmann, 2023) or visit the AMD website.

Submission Guidelines

Standard guidelines apply to papers sent in for this Special Issue. Manuscripts may be submitted as traditional papers or as Discoveries-through-Prose. Discoveries-through-Prose are crafted in more creative and engaging ways than traditional papers. When composing such manuscripts, we encourage authors to relax their use of traditional headings and traditional “academic writing” in order to create a compelling narrative from start to finish. More information about Discoveries-through-Prose can be found on the AMD website.

References

Ben-Menahem, S. M. 2024. Engaging practitioners in empirical exploration. Academy of Management Discoveries, 10(2): 155-162.

D’Aunno, T., Succi, M., & Alexander, J. A. 2000. The role of institutional and market forces in divergent organizational change. Administrative Science Quarterly, 45(4): 679-703.

DiBenigno, J. 2022. How idealized professional identities can persist through client interactions. Administrative Science Quarterly, 67(3): 865-912.

DiBenigno, J., & D’Aunno, T. 2024. A necessary prescription: How studies of healthcare can advance theory and practice. Administrative Science Quarterly. Research Curation.

Djukic, M., Jun, J., Kovner, C., Brewer, C., & Fletcher, J. 2017. Determinants of job satisfaction for novice nurse managers employed in hospitals. Health Care Management Review, 42(2): 172-183.

Everson, J., Lee, S. Y. D., & Adler-Milstein, J. 2016. Achieving adherence to evidence-based practices: Are health IT and hospital-physician integration complementary or substitutive strategies? Medical Care Research and Review, 73(6): 724–751.

Hilligoss, B., & Vogus, T. J. 2015. Navigating care transitions: A process model of how doctors overcome organizational barriers and create awareness. Medical Care Research and Review, 72(1): 25-48.

Hughes, A. M., Gregory, M. E., Joseph, D. L., Sonesh, S. C., Marlow, S. L., Lacerenza, C. N., Benishek, L. E., King, H. B., & Salas, E. 2016. Saving lives: A meta-analysis of team training in healthcare. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(9): 1266-1304.

Johns, G. 2001. In praise of context. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(1): 31-42.

Kohn, L. T., Corrigan, J. M., & Donaldson, M. S. 2000. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

LeBaron, C., Christianson, M. K., Garrett, L., & Ilan, R. 2016. Coordinating flexible performance during everyday work: An ethnomethodological study of handoff routines. Organization Science, 27(3): 514-534.

Lee, J. M., & Kapoor, R. 2017. Complementarities and coordination: Implications for governance mode and performance of multiproduct firms. Organization Science, 28(5): 931–946.

Luciano, M. M., Bartels, A. L., D’Innocenzo, L., Maynard, M. T., & Mathieu, J. E. 2018. Shared team experiences and team effectiveness: Unpacking the contingent effects of entrained rhythms and task characteristics. Academy of Management Journal, 61(4): 1403-1430.

Mayo, A. T. 2022. Syncing up: A process model of emergent interdependence in dynamic teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 67(3): 821-864.

Mayo, A. T., Myers, C. G., & Sutcliffe, K. M. 2021. Organizational science and health care. Academy of Management Annals, 15(2): 537-576.

Miller, C. C. 2024. Pirates, adventurers, and free spirits: The people of Academy of Management Discoveries. Academy of Management Discoveries, 10(1): 1-6.

Myers, C. G., Polsky, D., & Desai, S. 2022. The growing role of chief medical officers in major corporations. JAMA Health Forum, 3(7): e222194.

Perry, S. J., Richter, J. P., & Beauvais, B. 2018. The effects of nursing satisfaction and turnover cognitions on patient attitudes and outcomes: A three‐level multisource study. Health Services Research, 53(6): 4943-4969.

Pratt, M. G., Rockmann, K. W., & Kaufmann, J. B. 2006. Constructing professional identity: The role of work and identity learning cycles in the customization of identity among medical residents. Academy of Management Journal, 49(2): 235-262.

Ramanujam, R., & Rousseau, D. M. 2006. The challenges are organizational not just clinical. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(7): 811–827.

Reddy, A., Wong, E., Canamucio, A., Nelson, K., Fihn, S. D., Yoon, J., & Werner, R. M. 2018. Association between continuity and team-based care and health care utilization: An observational study of medicare-eligible veterans in VA patient aligned care team. Health Services Research, 53(2): 5201-5218.

Reiss-Brennan, B., Brunisholz, K. D., Dredge, C., Briot, P., Grazier, K., Wilcox, A., Savitz, L., & James, B. 2016. Association of integrated team-based care with health care quality, utilization, and cost. JAMA, 316(8): 826-829.

Rockmann, K. 2023. Embracing an exploratory mindset: How amd is changing the script of good science. Academy of Management Discoveries, 9(4): 419-423.

Rousseau, D. M., & Fried, Y. 2001. Location, location, location: Contextualizing organizational research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(1): 1-13.

Sheridan, B., Chien, A. T., Peters, A. S., Rosenthal, M. B., Brooks, J. V., & Singer, S. J. 2018. Team-based primary care. Health Care Management Review, 43(2): 115-125.

Trybou, J., Gemmel, P., & Annemans, L. 2016. The impact of economic and noneconomic exchange on physicians’ organizational attitudes. Health Care Management Review, 41(1): 75-85.

Valentine, M. A., & Edmondson, A. C. 2015. Team scaffolds: How mesolevel structures enable role-based coordination in temporary groups. Organization Science, 26(2): 405-422.

Westphal, J. D., Gulati, R., & Shortell, S. M. 1997. Customization or conformity? An institutional and network perspective on the content and consequences of TQM adoption. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42(2): 366-394.

Appendix

Reproduced from: Mayo, A. T., Myers, C. G., & Sutcliffe, K. M. 2021. Organizational science and health care. Academy of Management Annals, 15(2): 537-576.